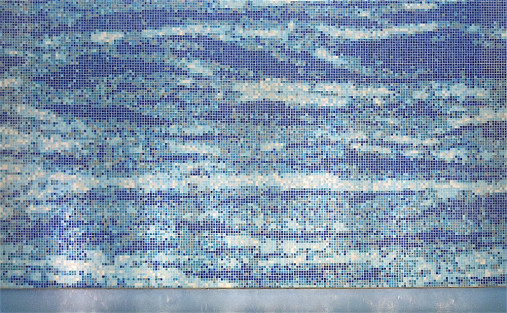

An area indoors with a water feature, some moving water that space users can see and hear, is one where design is doing good work.

Neuroscientists have identified a powerful link between seeing or hearing gently flowing water and achieving the sorts of objectives designers often have for people in spaces they develop—to perform professionally to full potential, to refresh mentally . . . basically to live their best lives.

Including water in interior spaces is an important tenet of biophilic design. Biophilic design is discussed in more detail here.

There’s lots of research indicating that water features inside are a plus, for example:

- White and colleagues investigated the influence of visible water (in lakes, rivers, fountains, etc.) on the restorative potential of natural and built environments (2010). Their work carefully assesses the experience of viewing water alone, water paired with either natural or built environments, and natural and built environments without visible water. They found that “as predicted, both natural and built scenes containing water were associated with higher preferences, greater positive affect [mood] and higher perceived restorativeness than those without water . . . Intriguingly, images of ‘built’ environments containing water were generally rated just as positively as natural ‘green’ space.” It is important to remember that because of the research methodology used, water elements in any of the images shown to participants took up at least 1/3 of the picture, but scales varied between images and one photo presented “featured a pigeon bathing in an urban fountain” while others were sweeping panoramas. White and teammates found the same effect whether water was naturally occurring, such as a river, or not (for example, a fountain).

- Cracknell’s (2012) work “suggest[s] that even watching an empty tank may be physiologically and emotionally restorative but that the presence of fish improves these effects further . . . the Medium biodiversity tank produced the most restorative effects but differences from Low biodiversity were rarely significant . . . given the pattern of data, we predict significant improvements during the next phase of restocking when biodiversity will increase yet further.” The researcher reports on the types and numbers of fish used in each test condition, but not the size of the aquarium. All study participants viewed the fish tank for 10 minutes before information was collected about the effects of the tanks on their psychological states.

- Research reported by the University of Exeter corroborates earlier studies indicating that seeing aquariums makes people feel calmer (“Aquariums Deliver Health and Wellbeing Benefits,” 2015). Cracknell, Pahl, and White determined that “viewing aquarium displays led to noticeable reductions in blood pressure and heart rate, and that higher numbers of fish helped to hold people's attention for longer and improve their moods. . . . Deborah Cracknell [who] conducted the study [states that]: ‘Fish tanks and displays are often associated with attempts at calming patients in doctors' surgeries and dental waiting rooms. This study has . . . provided robust evidence that 'doses' of exposure to underwater settings could actually have a positive impact on people's wellbeing.’"

- Clements and colleagues (2019) studied the implications of having aquariums present in a space, either live or on video. After a literature review they report that “Nineteen studies were included [in their analysis]. Two provided tentative evidence that keeping home aquaria is associated with relaxation. The remaining studies involved novel interactions with fish in home or public aquariums. Outcomes relating to anxiety, relaxation and/or physiological stress were commonly assessed; evidence was mixed with both positive and null [no relationship] findings. Preliminary support was found for effects on mood, pain, nutritional intake and body weight, but not loneliness. . . . Review findings suggest that interacting with fish in aquariums has the potential to benefit human well-being, although research on this topic is currently limited.”

- Yin and teammates studied the implications of being in indoor biophilic spaces using virtual reality (2020). They report that “Participants were randomly assigned to experience one of four virtual offices (i.e. one non-biophilic base office and three similar offices enhanced with different biophilic design elements) after stressor tasks. Their physiological indicators of stress reaction, including heart rate variability, heart rate, skin conductance level and blood pressure, were measured by bio-monitoring sensors. . . . We found that participants in biophilic indoor environments had consistently better recovery responses after stressor compared to those in the non-biophilic environment, in terms of reduction on stress and anxiety. Effects on physiological responses are immediate after exposure to biophilic environments with the larger impacts in the first four minutes of the 6-minute recovery process.” Also: “In the stressor period, participants were exposed to a virtual office with untidy conditions and background noises from traffic, machinery and household appliances. They were instructed to finish two stress induction tasks (i.e. memory task and arithmetic task).” Biophilic design elements utilized included plants, water (a fish tank), natural materials, biomorphic shapes, and views of nature, for example.

- Incorporating peaceful water features (visually and/or acoustically) into interior environments and providing views of gently moving nearby water optimize our wellbeing and cognitive performance. E

Water sounds are a plus in a space:

- Ratcliffe’s work indicates the value of nature soundtracks in particular contexts (2021). She determined via a literature review that “nature is broadly characterized by the sounds of birdsong, wind, and water, and these sounds can enhance positive perceptions of natural environments presented through visual means. Second, isolated from other sensory modalities these sounds are often, although not always, positively affectively appraised and perceived as restorative. Third, after stress and/or fatigue nature sounds and soundscapes can lead to subjectively and objectively improved mood and cognitive performance, as well as reductions in arousal. . . . not all nature sounds are regarded equally positively. . . . [for example] Bradley and Lang (2007) measured 167 sounds. . . . Some natural sounds, such as water and birds, scored relatively high on pleasure while others, such as growling, were rated as less pleasant. . . . . Hedblom et al. (2014) observed that combinations of bird sounds were rated as more pleasant than the sounds of a single species.”

- Buxton and colleagues (2021) reviewed published studies on the implications of hearing nature sounds. They determined that “natural sounds improve health, increase positive affect [mood], and lower stress and annoyance. . . . Our review showed that natural sounds alone can confer health benefits. . . . water sounds had the largest effect on health and positive affective outcomes, while bird sounds had the largest effect on alleviating stress and annoyance.”

- How restorative particular sounds are is not necessarily objectively determined (Haga, Halin, Holmgren, and Sorqvist, 2016): “Visiting or viewing nature environments can have restorative psychological effects, while exposure to the built environment typically has less positive effects. . . . Participants conducted cognitively demanding tests prior to and after a brief pause. During the pause, the participants were exposed to an ambiguous sound consisting of pink noise with white noise interspersed. Participants in the ‘nature sound-source condition’ were told that the sound originated from a nature scene with a waterfall; participants in the ‘industrial sound-source condition’ were told that the sound originated from an industrial environment with machinery; and participants in the ‘control condition’ were told nothing about the sound origin. Self-reported mental exhaustion showed that participants in the nature sound-source condition were more psychologically restored after the pause than participants in the industrial sound-source condition. One potential interpretation of the results is that restoration from nature experiences depends on learned, positive associations with nature; not only on hardwired responses shaped by evolution.”

“Aquariums Deliver Health and Wellbeing Benefits.” 2015. Press release, University of Exeter, http://www.exeter.ac.uk.

Rachel Buxton, Amber Pearson, Claudia Allou, Kurt Fristrup, and George Wittemyer. 2021. “A Synthesis of Health Benefits of Natural Sounds and Their Distribution in National Parks.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 118, no. 14, e2013097118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2013097118

Heather Clements, Stephanie Valentin, Nicholas Jenkins, Jean Rankin, Julien Baker, Nancy Fee, Donna Snellgrove, and Katherine Sloman. 2019. “The Effects of Interacting with Fish in Aquariums on Human Health and Well-Being: A Systematic Review.” PLoS ONE, vol. 14, no. 7, e0220524, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220524

Deborah Cracknell. 2012. “The Restorative Potential of Aquarium Biodiversity.” Bulletin of People-Environment Studies, vol. 39, Autumn, pp. 18-21.

Andreas Haga, Niklas Halin, Mattias Holmgren, and Patrik Sorqvist. 2016. “Psychological Restoration Can Depend on Stimulus-Source Attribution: A Challenge for the Evolutionary Account?” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 7, article 1831.

Eleanor Ratcliffe. 2021. “Sound and Soundscape in Restorative Natural Environments: A Narrative Literature Review.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 12, 570563, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.570563

Mathew White, Amanda Smith, Kelly Humphryes, Sabine Pal, Deborah Snelling, and Michael Depledge. 2010. “Blue Space: The Importance of Water for Preference, Affect, and Restorative Ratings of Natural and Built Scenes.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vo. 30, no. 4, pp. 482-493.

Jie Yin, Jing Yuan, Nastaran Arfaei, Paul Catalano, Joseph Allen, and John Spengler. 2020. “Effects of Biophilic Indoor Environment on Stress and Anxiety Recovery: A Between-Subjects Experiment in Virtual Reality.” Environment International, vol. 136, 105427, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105427