For more information on DLR Group visit www.dlrgroup.com.

Interest in data-backed actions that contribute to individual, community, and planetary health is on the rise. The burden of proof continues to scale across industries as consumers become wiser about potential “greenwashing” and misleading claims.

Greenwashing (or anything that humans view as an attempt to covertly manipulate their behavior) destroys not only credibility but also support for actions that might otherwise be popular. Humans have a fundamental need to feel in control of many aspects of their lives and to be respected by others and greenwashing acts counter to those needs.

How can we add information about sustainability and wellness outcomes to the built environment without adding noise, confusion, or distraction? And what kind of information will be most meaningful to occupants who may or may not have high expectations of the spaces they use? Why is letting people know about the sustainability of spaces used worth the effort?

Examples from Fields Besides Design

Anyone developing tools to communicate building sustainability achievements through visuals, can look to industries other than design for useful insights. The beauty and fashion industries are both full of options that allow consumers to access layered information on sustainaibility-related achievements… and both fields also offer cautionary tales of customer reactions to greenwashing. Purchasing platforms that allow sustainability filtering, labeling programs, or impact reporting to the customer are examples of how organizations can back sustainability claims with data in a transparent way.

What Is Design Saying Now About Sustainability?

Summarized claims of sustainable achievement presented to consumers are seldom partnered with supporting proof, like environmental impact reporting or real time resource usage data, but this generally unreported information –-when it is available—is increasingly factored into customers’ expectations and satisfaction with sustainable alternatives. Quick summaries are critical to grab attention, but do building users want or expect access to a deeper supporting information? Recent events indicate that some do; the explosion of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting is partly a cause and partly an outcome of elevating expectations and promoting multi-lensed audits.

In the case of the built environment, client and occupant expectations regarding sustainability and wellness appear to be stuck at “film on the window” or “plaque on the wall” status –in other words, a quick, static summary. These reports on achievement are typically located in the most prominent or public areas of the building and in shared spaces where users are asked to take specific actions to “help the building” continue operating as intended (ex. composting food waste in the kitchen). But static visual signage fades in impact over time and too many signs and words in a space can produce visual noise and increase visual complexity to stress inducing levels. What are some alternatives?

Education In and Beyond the Building

While many green building rating systems factor in user education as required for their success, one program stands out as it brings user understanding “beyond the lobby.” The Living Building Challenge requires the following sorts of user-facing education:

- A publicly available living building case study

- A publicly available copy of the building’s operations and maintenance manual

- Publicly available brochures that describe the project and its environmental features

- An annual open house

- An educational website

The list above is comprehensive – it spans mediums, frequency and familiarity of sharing, and audience types.

The broad range of education options is important because user education can drive change when it aligns with users' preferred codes of behavior and ways of living beyond a single building. Many of the campaigns to use materials without VOC issues, for example, originated after user education led to increased demand because of widespread health concerns. The effects of user education on the built environment are tempered at large scale by the requirement that designers respond to user sentiments. For example, a user can start to recycle at their own home whenever they want to but cannot sign off on the architectural plans for their new company offices - only a designer can do that. When educated users can influence design decisions or even the selection of designers, they're more likely to wind up with design teams and projects whose values on important issues align with their own.

Unfortunately, however, because of a lack of related user education, the Living Building Challenge continues to be perceived to be out of reach for many building owners and teams despite the International Living Future Institute making a case for feasibility regardless of owner type or building size. How can building users be afforded the same opportunity to understand regardless of the green building program? Should someone have to be on the design or client team to understand what sustainable achievements are realized and how they are attained?

Information Embedded in Spaces

DLR Group has implemented or observed several examples of sustainability communication tied to the building and resulting space, but using these solutions requires work on the part of users or demands their attention while they’re in the environment. It’s important we continue to iterate on tactics and methods for education, and this piece might expose a few new avenues for doing so.

Signs

While static signs can fade in impact if they seem irrelevant after the first reading, DLR Group is testing the enduring impact of physical signs (approximately the size of a sheet of letter paper) that tell the story of an achievement related to the building’s LEED certification throughout a building and are entertaining. Their design is based on anecdotal client information from comparable projects indicating that employees enjoy giving tours of the space to guests or new staff members, especially when they can point out humorous moments or fun facts people on their tours might not know.

For example, one sign prompts building users to learn an acronym: “EPD: electronic product design? Nope. EPD: engineering professional development? Nope. EPD: environmental product declaration. BINGO. This project collected 1.5 times the amount of EPDs required for the building products used to compose this space. Any product can have an EPD. EPDs help us learn about the embodied carbon footprint / life cycle data of well... anything!”

This example sign exposes users to technical terms in the hope that users viewing it will advocate for something similar from all spaces they use and teach others to value useful information.

Pictured: Snippet example and proposed implementation sketch

Symbolism

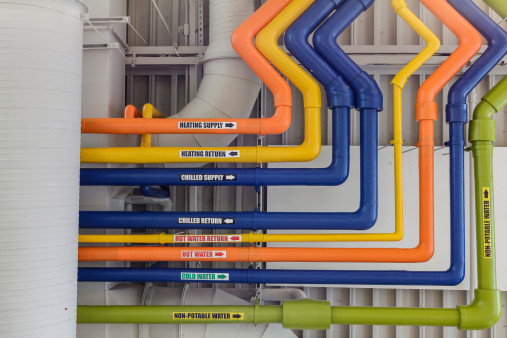

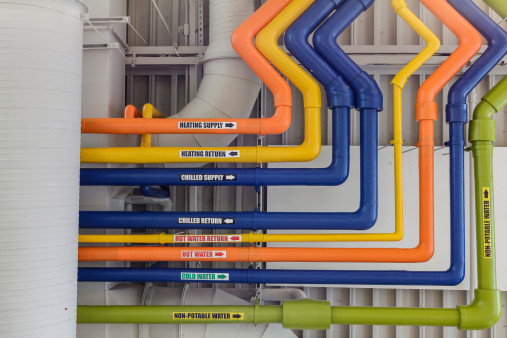

Pictured: Petersen Elementary School

Not all sustainability achievements have the same impact on the Earth’s health. Many rating systems have multiple levels of achievement (LEED Silver, LEED Gold, etc.) and achieving a higher reward level in these systems might not accurately align with earth friendly impacts; sometimes equal points can be earned from actions with very different long term implications. The challenge is determining what information supports more meaningful distinctions between levels of achievement and how occupants can be encouraged to understand these “value-to-the Earth” differences? We can look to solutions like the plumbing pipe codification in an elementary school (designed by DLR Group). Colors in use denote different systems and the same color system is utilized throughout the building, to build familiarity with the plumbing piping’s role in sustainability performance. DLR Group has also experimented with custom raised access floor solutions that allow users to view a purple pipe system. Purple pipe is often indicative of the reclaimed water system. Design solutions like these bring visibility and salience to building systems that are typically invisible – and yet play a vital role in the sustainable achievement.

Pictured: example of proposed visibility to a water reclamation system (aka: “purple pipe”)

Digital Displays

Pictured: https://sonraiapp.com/

Digital displays do work, particularly those that are dynamic and respond quickly to actions taken – if there is a lag that confounds understanding the effects of actions taken (varying a ventilation rate’s effects on energy use, for example), the displays become much less effective. Remember the discussions several years ago in the popular press of the “Prius Effect” i.e., car owners modifying their behaviors in real time based on info on their dashboards? In addition to being timely, it is also desirable for a display to present information related to not only the behaviors of the user group for a particular space but also information related to the actions of other groups in areas that those other groups manage – humans are regularly pretty competitive so allowing comparisons from one group’s actions to another’s (or in a different context, from one household to another) can spur more environmentally responsible actions. Any signage must follow requirements for readability (by people walking or standing, for example) and similar prerequisites.

One method DLR Group has tested for digital displays of information is an Indoor Air Quality monitoring program, called SONRAI. Like other digital dashboards and apps, SONRAI draws together real-time indoor air quality data into a format that is easier for users to understand. An app or dashboard that can clearly communicate information to people in a way that helps them take action is a strong addition to a space, because it helps building occupants participate in creating greater impact.

Early, rapid adoption of the Architecture 2030 commitment led to be a similar exercise at many firms: determining how to quickly distill a complex topic and educate teams and clients at scale.

When DLR Group became a A2030 signatory, the firm developed an electronic 2030 Scoreboard to make data from AIA’s 2030 Design Data Exchange (DDx) visible across offices. The Scoreboard also tied DDx data to internal project metrics to help connect larger sustainability moves to employees’ everyday actions and jobs. However, the digital scoreboard didn’t address the different office cultures at the firm’s 30+ locations. Each office deals with different climate zones and building codes so it made sense to create region-specific ways of celebrating progress towards Architecture 2030.

DLR group created unique interactive physical scoreboards to test if play could lead to better understanding and adoption of environmentally responsible behaviors across teams. A physical installation can powerfully communicate information nonverbally to groups that is meaningful to them and that is, ideally, consistent with their perceptions of organizational culture. These “silent signals” are an important way to relay information and are seen as more representative of an organization’s true position on issues than stances presented through easier to change communication channels, such as values statements. Storytelling and play can have a significant effect on users’ sense of belonging and influence on their perceptions of organizational values, particularly when storytelling and play opportunities are consistent with organizational culture.

Pictured: Denver’s 2030 scoreboard

Pictured: Seattle’s 2030 scoreboard

Call to Action

As ESG reporting and other sustainability frameworks are adopted by more firms, the quantity and quality of sustainability-related data reported are both increasing – but several studies show that actual performance and impact are plateauing. This is because of both the limitations of current building codes and reporting technologies as well as the need to create design solutions that empower users to change their behavior and actually have greater impact over time.

At the same time, much of the developed world is dealing with information and choice overload, especially regarding digital technologies. The building industry still needs engaging ways for users to interact with data—ways that don’t demand visual attention, cause distraction, or ask for significant extra effort and thereby create barriers to use—but do provide actionable information. Data shared via signage, etc., needs to be relevant to users who already care about sustainability, as well as those who aren’t necessarily educated on and aligned with sustainability goals.

No one firm has all the answers – and that’s OK. It is going to take industry-wide action to effectively move the needle on sustainable outcomes, and firms that collaborate within and outside the architecture industry stand to create lasting impact.

Appendix: Why is Letting People Know About Sustainability Worth the Effort?

Sustainable design is clearly good for the planet. Neuroscience research also shows that it’s great for people’s mental and physical health, their wellbeing and cognitive performance, particularly when people know that they’re experiencing green design.

Cognitive Benefits of Green Design, the Basics

Environmentally responsible design has positive effects on our mental and physical states and that can boost our cognitive performance.

People generally seem to get a psychological boost from being in spaces that are designed to be environmentally-responsible.

Leaman and Bordass (2007) reviewed occupant surveys from 177 buildings in the United Kingdom and learned that people working in environmentally responsible buildings feel better about the image presented by their building and the way the building meets their needs than people who are working in conventional buildings. They are also more tolerant of comfort-related problems (e.g., temperature, ventilation, noise, lighting) in green buildings than workers in conventional buildings are of similar issues. More details from the Leaman and Bordass research:

- The range of expressed user satisfaction with comfort-related features is wider for green-intent buildings than for conventional buildings—green buildings tend to have the highest or the lowest scores for environmental satisfaction, for example.

- The green buildings scores for design and image are particularly high when compared to the conventional buildings, but the authors point out that the green buildings are generally newer than the conventional buildings surveyed.

- “Occupants tend to be more ‘forgiving’ when features that they intrinsically like are present, as they tend to be in green buildings (e.g., views out, shallower plan forms, more control and better use of natural light and often more care taken in their . . . design and management generally).”

- “Where design intent is made clearer to users, that is when users understand how the building is supposed to work, they are more likely to give the benefit of the doubt.”

- “If they like the design, and their experience of using the building is generally good and supportive of their work tasks, even if there are chronic problems with it, users will tend to be more tolerant.”

Leaman and Bordass indicate that their research in green buildings was done in spaces with green intent; this means that green issues were mentioned in the design brief. These buildings, as built, may not be truly more environmentally responsible than conventional buildings.

Galen Cranz and colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, conducted a post-occupancy evaluation of a new green office building (the David Brower Center, Berkeley, CA; 50,000 square feet; LEED Platinum; Cranz, Lindsey, Morhayim, and Lin, 2014). The POE literature review is very complete and carefully assesses related studies: “even though prior research shows that user reaction to specific features of green buildings is negative or mixed (lighting and thermal comfort varies across green buildings, and acoustics are negatively rated in most cases), overall building satisfaction is high. . . . This is probably because of the buildings’ green label: It seems that people feel good about being affiliated with a green building.” Data collected indicated that “tall windows and solar panels, communicated the building being green. However, other components of the building program, such as gallery space . . . and rentable areas, that were intended to inspire the public about sustainability were not visible and attractive enough, and therefore did not serve well in communicating to the visitors the building’s effort to be green.” Bike racks were also identified as a building feature that signals green design.

The positive repercussions of green design for assessments extends beyond places. Sorqvist, Haga, Holmgren, and Hansla (2015) report that their empirical research has shown that when “48 university students were asked to undertake a color discrimination task adjacent to a desktop lamp that was either labeled ‘environmentally friendly’ or ‘conventional’ (although they were identical). . . . The light of the lamp labeled ‘environmentally friendly’ was rated as more comfortable. Notably, task performance was also better when the lamp was labeled ‘environmentally friendly’.” Task performance was objectively measured, differences reported are not due to differences in perceptions of study participants.

Allen and team (2015) reviewed completed studies of green buildings and found “better indoor environmental quality in green buildings versus non-green buildings, with direct benefits to human health for occupants of those buildings.” The researchers also found that people working in green buildings are more satisfied with workspaces, indoor air quality, and cleanliness/maintenance at their workplaces than people working elsewhere. Productivity in green buildings also seems to be higher. Some of the detailed findings reported by Allen and colleagues include: “green buildings were associated with lower employee turnover and a decrease in the length of open staff positions. In a hospital setting, [studies] noted improved quality of care in green buildings, fewer blood stream infections, improved record keeping, and lower patient mortality.”

Ventilation consistent with green design has the potential for positive effects on “breather” welfare and wellbeing, regardless of the type of place in which it is implemented. Most ventilation related research has, however, been done in workplaces.

The MacNaughton team (2017) “recruited 109 participants from 10 high-performing buildings (i.e. buildings surpassing the ASHRAE Standard 62.1–2010 ventilation requirement and with low total volatile organic compound concentrations) in five U.S. cities. In each city, buildings were matched by week of assessment, tenant, type of worker and work functions. A key distinction between the matched buildings was whether they had achieved green certification. Workers were administered a cognitive function test of higher order decision-making performance twice during the same week while indoor environmental quality parameters were monitored. Workers in green certified buildings scored 26.4% [significantly] higher on cognitive function tests . . . and had 30% fewer sick building symptoms than those in non-certified buildings. These outcomes may be partially explained by IEQ factors, including thermal conditions and lighting, but the findings suggest that the benefits of green certification standards go beyond measurable IEQ factors.” Education and job category/level were eliminated as explanations for the effects found via statistical tools.

Allen and team (2016) learned, by studying people who worked in a green environment for 6 full days, that higher order cognitive function was enhanced in the environmentally responsible structure. More details on the test conditions: study participants “On different days . . . were exposed to IEQ conditions representative of Conventional (high volatile organic compound (VOC) concentration) and Green (low VOC concentration) office buildings in the U.S. Additional conditions simulated a Green building with a high outdoor air ventilation rate (labeled Green+) and artificially elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) levels independent of ventilation.” Allen and colleagues found that “On average, cognitive scores were 61% higher on the Green building day and 101% higher on the two Green+ building days than on the Conventional building day. . . VOCs and CO2 were independently associated with cognitive scores. . . . Cognitive function scores were significantly better in Green+ building conditions compared to the Conventional building conditions for all nine functional domains.” At the sorts of carbon dioxide levels regularly found in indoor spaces (approximately 950 ppm), performance on 7 of the 9 cognitive tests administered was lower than on the same tests at lower concentrations of carbon dioxide. Examples of the cognitive functions tested: decision making, developing strategies and responding to crises. Study participants had a range of backgrounds including design and architecture, computer programming and engineering, as well as marketing and general management.

Terrapin Bright Green released a review of the research on how in-building ventilation influences human physical and emotional wellbeing (Walker and Browning, 2019). The ventilation report’s website notes that “Poor indoor air quality diminishes cognitive functioning. . . . Indoor air quality management remains an industry challenge as efforts to improve air quality . . . often come at the expense of energy performance.” In the report itself, Walker and Browning state that “symptoms associated with poor indoor air quality include headaches, fatigue, trouble concentrating and irritation of the eyes, nose, throat and lungs. Studies have also linked long-term air pollutant exposure to impaired memory, degraded cognitive performance, disrupted sleep, increased rates of asthma, heart disease, and certain cancers. . . . Wargocki, Wyon, and Fanger estimated a 1.9% increase in office task performance for every two-fold decrease of the pollution load.” Strategies to clean indoor air are discussed by Walker and Browning. For example, “In comparison to a single-pass air ventilation strategy, the use of air-cleaning molecules to manage pollutants allows buildings to recirculate air that has already been temperature- and humidity-conditioned. . . . Carbon dioxide can be an important determinant of cognitive performance indoors.”

Green roofs can be viewed from any sort of space and doing so gives us a cognitive boost. As with ventilation, most research related to green roofs has also been done in workplaces. For example, scientists have found that looking at green roofs even very briefly has benefits (Lee, Williams, Sargent, Williams, and Johnson, 2015). Lee and colleagues learned that “micro-breaks spent viewing a city scene with a flowering meadow green roof . . . boost sustained attention. Sustained attention is crucial in daily life and underlies successful cognitive functioning. . . . Participants who briefly [for 40-seconds] viewed the green roof [did a better job on cognitive tasks than] participants who viewed the concrete roof."

Additional Findings, Green Workplace Design

The World Green Building Council has written, and is distributing free at the website noted below, an important guide for green designers and anyone else interested in the business case for environmentally responsible workplaces (2016). Through an overview of published research and seven geographically dispersed case studies as well as “seven spotlights on specific countries, companies, and research leaders,” the Council details the economic value of designing green. Case studies included provide detailed, and quantified, project-specific information.

Among the research findings presented are “Eight Features That Make Healthier and Greener Offices”:

- “Indoor air quality and ventilation. Healthy offices have low concentrations of carbon dioxide, VOCs and other pollutants, as well as high ventilation rates. Why? 101% increase in cognitive scores for workers in green well-ventilated offices.

- Thermal comfort. Healthy offices have a comfortable temperature range which staff can control. Why? 6% fall in staff performance when offices are too hot and 4% if too cold.

- Daylighting and lighting. Healthy offices have generous access to daylight and self-controlled electrical lighting. Why? 46 minutes more sleep for workers in offices near windows.

- Noise and acoustics. Healthy offices use materials that reduce noise and provide quiet spaces to work. Why? 66% fall in staff performance as a result of distracting noise.

- Interior layout and active design. Healthy offices have a diverse array of workspaces, with ample meeting rooms, quiet zones, and stand-sit desks, promoting active movement within offices. Why? Flexible workspaces help staff feel more in control of their workload and engender loyalty.

- Biophilia and views. Healthy offices have a wide variety of plant species inside and out as well as views of nature from workspaces. Why? 7 -12% improvement in processing time at one call centre when staff had a view of nature.

- Look and feel. Healthy offices have colours, textures, and materials that are welcoming, calming and evoke nature. Why? Visual appeal is a major factor in workplace satisfaction.

- Location and access to amenities. Healthy offices have access to public transport, safe bike routes, parking, and showers, and a range of healthy food choices. Why? 27 million Euros savings through cutting absenteeism as a result of Dutch cycle-to-work scheme.

Employee engagement. Healthy offices have employees that are regularly consulted and that feedback is used to drive continuous improvement.”

Research by the General Services Administration (GSA) provides additional evidence that working in an environmentally responsible workplace has positive psychological implications. The GSA conducted a post-occupancy evaluation of 12 environmentally responsible buildings in its portfolio (2008). Their findings, that these structures are more earth-, budget-, and user-friendly, are consistent with the existing body of research on green structures. The GSA study was unusual because it assessed the environmental, financial, and psychological implications of building design features simultaneously: “The study found that GSA’s green buildings outperform national averages in all measured performance areas—energy, operating costs, water use, occupant satisfaction, and carbon emissions. The study also found that GSA’s LEED Gold buildings, which reflect a fully integrated approach to sustainable design—addressing environments, financial, and occupant satisfaction issues in aggregate—achieve the best overall performance. . . . The 12 buildings selected reflect different US regional climates, a mix of uses (courthouses and offices), and a mix of build-to-suit leases and federally owned buildings.”

The financial and environmental findings of the GSA study are straightforward and predictable, while the findings related to user satisfaction are more interesting. The buildings assessed scored above average on polls of occupant satisfaction: “The study provides important new evidence that occupant satisfaction is higher in sustainably designed buildings. Occupant satisfaction is important because it correlates with personal and team performance. That often means higher productivity and creativity for an organization.” For more on links between satisfaction and performance, read this article.

Dreyer and colleagues (2018) set out to learn more about how green buildings influence wellbeing. They collected data at a LEED gold certified building in Canada, measuring (among other things) hedonic, eudaimonic (EWB), and negative wellbeing (NWB). The researchers “explored physical features (e.g., air quality, light), and social features (e.g., privacy), as well as windows to the outside. . . . overall satisfaction with indoor environmental features predicted all aspects of employees’ wellbeing. That is, employees experiencing higher levels of satisfaction with indoor environmental features also reported higher levels of hedonic and EWB and lower levels of NWB. . . . All aspects of wellbeing were significantly correlated with all aspects of environmental features. Thus, higher satisfaction with social and physical features and with a view outside were related to higher levels of hedonic and EWB and to lower levels of NWB. . . . these findings suggest that one’s workplace environment could significantly affect not just fleeting emotional states, pleasure attainment and emotional pain reduction (hedonic and NWB) but also one’s sense of meaning and self-actualization (EWB).” Additional project related details: the new building featured open offices configured to team needs and closed meeting rooms. Hedonic wellbeing was calculated via responses to questions about positive experiences/feelings and general life satisfaction. EWB was determined via answers to questions such as “’I lead a purposeful and meaningful life’ and ‘I actively contribute to the happiness and wellbeing of others.’” NWB was determined via answers to questions about negative experiences/feelings and about feeling anxious and/or depressed in the last 2 weeks.

Further research linking green design to positive business outcomes includes:

- Leder, Newsham, Veitch, Mancini, and Charles carefully examined data collected via two large field studies to learn more about how workplace design and job satisfaction are related (2016). They report that “The first study focused on open-plan offices in nine conventional buildings, whereas the second encompassed open-plan and private offices in 24 buildings (12 green and 12 conventional). . . . Satisfaction with acoustics and privacy was most strongly affected by workstation size [larger size, more satisfaction] and office type [higher if full-height walls and a door]; satisfaction with lighting was most strongly affected by window access [in one’s workstation] and glare conditions; and satisfaction with ventilation and temperature was most strongly affected by pollutant concentration. Occupants of green buildings rated all aspects of environmental satisfaction more highly. . . . job satisfaction was most strongly affected by pollutant concentration and office type [higher if full-height walls and a door].” It is important to note that “the physical conditions in all buildings were within ranges of prevailing recommended practices” and “the linkages between an improved indoor environment and better job satisfaction and other organizational productivity metrics are well established, and minor improvements in organizational productivity can have large payoffs.”

- Newsham and co-workers (Newsham, Birt, Arsenault, Thompson, Veitch, Mancini, Galasiu, Gover, Macdonald, and Burns, 2013) conducted a post-occupancy review of twelve green buildings in Canada and the northern United States. Newsham and colleagues found that “Green buildings exhibited superior performance compared with similar conventional buildings. Better outcomes included: environmental satisfaction, satisfaction with thermal conditions, satisfaction with the view to the outside, aesthetic appearance, less disturbance from heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) noise, workplace image, night-time sleep quality, mood, physical symptoms, and reduced number of airborne particulates.” The researchers found that “a variety of physical features led to improved occupant outcomes across all buildings, including: conditions associated with speech privacy, lower background noise levels, higher light levels, greater access to windows, conditions associated with thermal comfort, and fewer airborne particulates.”

- Bangawal, Tiwari, and Chamola also linked green design and important workplace outcomes (2017). The researchers “examine[d] how workplace design features of a green building contribute to the formation of employee organization commitment (OCM) through better job satisfaction (JST) within employees. . . . a theoretical model was proposed for investigation. Three putative paths linking workspace (WSP) to JST, departmental space (DSP) to JST, and JST to OCM were then tested relying on survey data . . . collected from three Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)-certified companies. . . . Significant evidences were witnessed in support of all three purposed paths.” Job satisfaction has been linked to professional performance, as discussed here.

- Newsham, Veitch, and Hu confirm that building green workplaces is good for both the health of the planet and the professional experiences of the people who work in them (2017). The scientists describe their research: “Data on . . . engagement, job satisfaction, job performance, and facility complaints for thousands of employees of a large Canadian financial organization were analysed to explore differences in outcomes between those working in green-certified office buildings and those in otherwise similar conventional buildings. Overall, green buildings demonstrated higher scores on survey outcomes related to job satisfaction, value to clients and stakeholders, evaluation of management, and corporate engagement. There was also a tendency for manager-assessed job performance to be higher in green buildings. Nevertheless, not all green buildings outperformed all conventional buildings, and superior performance was not exhibited on all outcomes examined.” The researchers provide additional information on the buildings where data were collected: “For each green building [LEED certified at some level] a matched conventional building was sought, and buildings pending green certification were excluded from the matching process. . . . The initial matching choices were based on building location (and thus similar regional conditions and climate), building age (of original construction date, not most recent renovation), and size.” Newsham, Veitch, and Hu believe that employees know if their workplaces are LEED certified.

- Newsham and Veitch lead a team that produced an important review of workplace design research, and much of the information they collected relates directly to green design (Newsham, Veitch, Zhang, Galasiu, Henderson, and Thompson 2017). Some highlights of their work: “In this report we have successfully demonstrated that better buildings strategies (e.g., improved ventilation, enhanced lighting conditions, green building certification measures) provide benefits to multiple organizational productivity metrics at levels similar to other corporate strategies. . . . The metrics used in this report are: absenteeism, employee turnover intent, self-assessed performance, job satisfaction, health and well-being (symptoms and overall), and complaints [to] the facilities manager. We developed benchmarks for each of these metrics, and compared the effects of better buildings strategies to other, commonly understood and practiced corporate strategies typically deployed to improve these same metrics. These strategies include: office type (private versus open-plan), workplace health programs, bonuses, and flexible work options. . . . Our results were derived from an exhaustive review and synthesis of high-quality published information from several disciplines, based on research conducted in real organizations in large office, or ’office-like’ buildings. In total, more than 4,000 abstracts, and 500 full publications were reviewed.”

- Lee and Guerin comprehensively explored the relationship between indoor environmental quality (air, thermal, and lighting), job performance and environmental satisfaction in five office types in LEED certified buildings (2010). The office types involved were private enclosed, private shared, open-plan with cubicle walls over five feet high, open-plan with cubicle walls shorter than five feet tall, and open-plan offices with no partitions (also known as bullpens). The researchers determined that “IAQ enhanced workers’ job performance in enclosed private offices more than both high cubicles and low cubicles. All four office types had higher satisfaction with the amount of light and visual comfort of light as well as more enhancement with job performance due to lighting quality than high cubicles.” In addition, “The study findings suggest a careful workplace design considering the height of partitions in LEED-certified buildings to improve employee’s environmental satisfaction and job performance.” In particular, Lee and Guerin mentioned using transparent or translucent panels near the top of the five-foot high partitions to alleviate some of the issues raised by the higher panels, since they would allow light to spread into the cubicles. More ambient lighting and more localized lighting control in open-plan offices with cubicles were also presented as potentially viable ways to eliminate issues found.

Thatcher and Miner investigated how employee attitudes changed after moves from traditional office buildings to green ones (Thatcher and Miner, 2014). They found that “high-level organizational measures were not notably affected by the move. Changes were, however, seen in physical well-being and perceived environmental comfort. The primary drivers were air quality and lighting.”

Data collected in Jordan illustrate the complexities of moving into certified-green offices from other types of structures (Elnaklah, Walker, and Natarajan, 2021). Researchers report that “localised green building codes, especially in the developing world, often do not systematically recognise IEQ or health as crucial issues. . . . we follow 120 employees of a single organisation as they transition from four conventional office buildings to the first green building (GB), designed to the local Jordanian Green Building Guide. . . . Statistically significant differences in thermal conditions, positively biased towards the GB, were observed across the move, and this enhanced occupant thermal comfort. Surprisingly, no significant improvement in occupant perception of air quality, visual and acoustic comfort was detected after moving to the GB, while odour, mental concentration, and glare were perceived to be poor in the GB. . . . our results support the growing concern that green buildings may create unintended consequences in terms of occupant comfort and health in the pursuit of a better thermal environment and energy efficiency.”

LoMonaco-Benzing and Ha-Brookshire, in a study published in Sustainability, investigated links between Millennials’ decisions to leave firms and gaps they identified between their employers’ stated values and actions (“’Values Gap’ in Workplace Can Lead Millennials to Look Elsewhere,” 2017). The researchers found that “one reason young workers choose to leave a firm is because they find a disconnect between their beliefs and the culture they observe in the workplace. ‘We were interested in workers’ values regarding sustainability and corporate sustainability practices and whether a gap existed,’ said Rachel LoMonaco-Benzing, a doctoral student in the MU College of Human Environmental Sciences. ‘Not only did we find a gap, but we also found that workers were much more likely to leave a job if they felt their values were not reflected in the workplace.’ . . . ‘Fewer people of this generation are just looking for a paycheck,’ Ha-Brookshire said. ‘They have been raised with a sense of pro-social, pro-environment values, and they are looking to be engaged. If they find that a company doesn’t honor these values and contributions, many either will try to change the culture or find employment elsewhere.’”

The United States Green Building Council (USGBC) asked Porter Novelli, a public relations firm, to investigate employee experiences in LEED-certified green buildings and elsewhere (“Employees are Happier, Healthier and More Productive in LEED Green Buildings,” 2018). The researchers found, after surveying 1,001 people working in the US in office buildings (employed by others or self-employed), that “More than 90 percent of respondents in LEED-certified green buildings say they are satisfied on the job and 79 percent [of all employees] say they would choose a job in a LEED-certified building over a non-LEED building. . . . 85 percent of employees in LEED-certified buildings also say their access to quality outdoor views and natural sunlight boosts their overall productivity and happiness, and 80 percent say the enhanced air quality improves their physical health and comfort. . . . 93% of those who work in LEED-certified green buildings say they are satisfied on the job. . . . 81% of those who work in conventional buildings say they are satisfied on the job.”

Giving workers control over dimming the lighting levels in their workspaces is a good idea (Newsham, 2007). Workers who can control the dimming of lighting levels at their workstations modify lighting levels in ways that consume much less energy. In addition, Newsham cites research indicting that “there is growing evidence that individual dimming controls improve occupant satisfaction” and that individual dimming control may improve “some aspects of performance” by workers.” The benefits of providing people with control over their physical environment are discussed here.

Research at the Center for the Built Environment (2007) produced results very similar to Newsham (2007). When people working in offices are given control of the lighting fixtures in their work areas, via a wireless control system, energy use drops dramatically and employees have a positive reaction to influencing the lighting levels in their workplaces. Researchers from the Center for the Built Environment report that when workers were given control over lights above workstations, conference areas, and filing areas, “Over a period of two months, we recorded the use of lights with the wireless controls and have measured a 65% reduction in lighting energy use compared with the pattern of use prior to the installation. In addition, occupants were enthusiastic about having personal control over their lighting.”

Chraibi and colleagues (2019) investigated employee responses to dynamic workplace lighting that dims over a workstation when the person working there leaves their seat and brightens when someone returns to that workspace. Installing dynamic lighting can be important because “Sensor-triggered control strategies can limit the energy consumption of lighting.” Via data collected in a mock-up office, the researchers learned that when “the participants performed an office-based task [and] the luminaire above the actors’ desk was dimmed from approximately 550 lx to 350 lx (average horizontal illuminance), and vice versa. . . . the noticeability of light changes due to dimming, increases when fading times become shorter. Dimming with a fading time of at least two seconds was experienced as acceptable by more than 70% of the participants.” During the data gathering periods there was “dimming up when occupancy is detected and diming down when a desk becomes unoccupied.” Of 6 lights in the test area, the intensity of only one varied, the light right above the workstation of a confederate of the researcher who entered or left the test area as instructed by the researchers. Data were collected from people sitting near that confederate and the lights remained on above the desks of the people answering the investigators’ questions. There was no natural light in the test area.

Cole, Coleman, and Scannell (2021) probe people’s relationships with green buildings. Via a literature review focused on non-residential buildings, the Cole-lead team link positive affect, or being in a good mood, with biophilic design: “Positive affect may be generated by buildings with biophilic design. . . . [literature reviewed] also pointed to the possibility that certain elements of green buildings could detract from the formation of place attachment. For example, natural ventilation, open-plan spaces, and hard surfaces contribute to poor speech privacy, and thus potentially interfere with an occupant’s productivity. . . . . Place attachment can enhance short-term individual wellbeing and quality of life, and can increase pro-environmental behaviors and community resilience. . . . To enhance place attachment for occupants, designers may additionally include abundant connections to nature, make the building’s environmental performance visible to occupants, support an array of eco-minded behaviors within the building, and ensure physiological comfort for occupants. This support for physical and psychological human wellbeing, together with design that enhances positive social practices within buildings, could result in places that better sustain both people and natural environments.”

It’s important to acknowledge that not all research findings on green design are resoundingly positive. Altomonte, Schiavon, Kent, and Brager (2019) studied alignment between green building ratings and space user satisfaction. They analyzed data from “a subset of the Center for the Built Environment Occupant Indoor Environmental Quality survey database featuring 11,243 responses from 93 Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)-rated office buildings.” Their analyses indicated that “the achievement of a specific IEQ credit did not substantively increase satisfaction with the corresponding IEQ factor, while the rating level, and the product and version under which certification had been awarded, did not affect workplace satisfaction.” This study is important because “Particularly in the workplace, the satisfaction of building occupants with the qualities of their indoor environment has been associated with their health and wellbeing . . . self-assessed job performance . . . . and behaviour.” Among the recommendations to designers and building managers presented by the Altomonte team: “personal control can provide significant opportunities for enriched comfort, energy performance and enhanced satisfaction with the indoor environment.”

Research by Schiavon and Altomonte also indicates that users of LEED buildings are not necessarily more satisfied with their workplaces than individuals working in non-LEED structures (2014); clearly many design decisions, beyond the one to “green” a structure influence experience. As Schiavon and Altomonte relate, “Occupant satisfaction in office buildings has been correlated to the indoor environmental quality of workspaces, but can also be influenced by factors distinct from conventional IEQ parameters such as building features, personal characteristics, and work-related variables.” Previous work by this research team has shown that “when evaluated comprehensively, there is not a practically significant influence of LEED certification on occupant satisfaction.” In their new study Schiavon and Altomonte report that “tendencies were found [i.e., very small differences were identified statistically] showing that LEED-rated buildings may be more effective in providing higher satisfaction in open spaces rather than in enclosed offices, in small rather than in large buildings, and to occupants having spent less than one year at their workspace rather than to users that have occupied their workplace for longer. The findings suggest that the positive value of LEED certification from the point of view of occupant satisfaction may tend to decrease with time.”

Urban and Sailer (2018) investigated the relationship between workplace green building certification and occupant satisfaction. They “analyz[ed] DGNB (German Green Building Council), BREEAM, and LEED certification and rating systems and match[ed] this with quantitative research into office buildings’ occupant satisfaction. The aim [was] to explore whether highly rated buildings are also perceived as excellent by users. . . . this research [the reported research] focus[ed] on the socio-cultural rating criteria within the DGNB system.” Data from a post-occupancy evaluation at a DGNB certified office building indicated that “an excellent Green Building rating does not allow the prediction of high occupant satisfaction within a certified building.”

Rashid and colleagues did not identify a relationship between green workplace design and perceptions of organizational image (OI) (Rashid, Spreckelmeyer, and Angisano, 2012). After surveying people working in a Gold-level LEED-certified public building, they found that “the occupants certainly appreciated the environmental design features of the buildings. These features had played an important role in determining how satisfied the occupants were with individual workspaces, departmental spaces, and the building. These environmental design features also made the occupants more environment-conscious, even though these features did not help improve their assessment of OI. In other words, even in a case where the ‘green’ building and the organization that occupies it are treated as an integrated system with the occupants being aware of the environmental-friendliness of the building, the building may not help improve the occupants’ assessment of OI.” It is important to note that all data in the Rashid study were collected from a single set of buildings, where other conditions may have influenced perceptions of OI.

In summary: Nurick and Thatcher (2021) conducted an extensive literature review and report that studies published “link[s] GBFIs [green building features and initiatives in office buildings] to increased individual productivity and organizational performance which results in increased building value, thus justifying the initial capital expenditure for the implementation of GBFIs.”

Benefits of Earth Friendly Design in Places Besides Workplaces

- Students attending schools constructed using principles outlined in the US Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program perform at a higher level academically, miss fewer school days, and in general are healthier (Kats, 2006). As Kats states, “based on a very substantial data set . . . a 3-5% improvement in learning ability and test scores in green schools appears reasonable and conservative. It makes sense that a school specifically designed to be healthy, and characterized by more daylighting, less toxic materials, improved ventilation and acoustics, better light quality and improved air quality would provide a better study and learning environment.”

- Bernstein, Russo, and Laquidara-Carr (2013) “looked at green in both new construction/major renovations and retrofits/operational improvements,” and gathered information from school personnel, finding that “Two-thirds report that their school had an enhanced reputation and ability to attract students due to their green investments; 91% of K-12 schools and 87% of higher education state that their green schools increase health and well-being; 74% of K-12 and 63% of higher education respondents report improved student productivity.”

- Research indicates that attending a school that’s been designed in an environmentally responsible way supports developing the knowledge necessary for green living (“School Buildings Designed as ‘Teaching Green’ Can Lead to Better Environmental Education,” 2016). Cole found that “students who attend school in buildings specifically designed to be ‘green’ [‘teaching green’ schools] exhibit higher levels of knowledge about energy efficiency and environmentally friendly building practices. . . . ‘Teaching green’ schools include a variety of design features to immerse students in an environmentally friendly atmosphere. These features can include open-air hallways, which greatly reduce heating and cooling costs; exposed beams and girders where students can see the materials required to erect such large structures; dedicated waste and recycling spaces that are easily accessible; and the use of recycled and repurposed construction materials.”

- In Denmark, Hansen, Gram-Hanssen, and Knudsen probed human behavior in energy efficient and energy inefficient homes (2018). They studied “administrative” data and survey responses from people living in single-family homes, learning that “perceived indoor temperature correlate with building characteristics, e.g. energy efficiency of the building envelope. . . . building characteristics are found to be less influential on the frequency of opening windows. The results indicate that occupants dress warmer and keep lower temperatures in energy-inefficient houses.” Information collected suggests that “window-opening habits in general are not strongly related to comfort.” They may “instead [be] entangled in many everyday practices such as cooking and cleaning. . . . [and] might also reflect that people open windows to get fresh air in and to be in contact with the outside, independent of whether their house has mechanical ventilation which should take care of adequate indoor environment from a technical point of view.” Also, “occupants living in more energy-efficient houses tend to report that they have a higher indoor temperature. The survey asked what occupants think of their temperature compared with others. Respondents were purposely not asked about their exact temperature or their comfort temperature.”

- Spendrup, Unter, and Isgren conducted research linking certain sounds and sustainable behavior (2016). They report that “Nature sounds are increasingly used by some food retailers to enhance in-store ambiance and potentially even influence sustainable food choices.” Research the Spendrup team conducted showed that “nature sounds positively and directly influence WTB [willingness to buy] organic foods in groups of customers (men) that have relatively low initial intentions to buy. . . . our study concludes that nature sounds might be an effective, yet subtle in-store tool to use on groups of consumers who might otherwise respond negatively to more overt forms of sustainable food information.”

- Susskind’s research on consumer responses to sustainable design elements can be applied in contexts beyond the hotel guest rooms in which it was conducted. Susskind (2014) learned that “Subtle energy saving changes in guest rooms did not diminish satisfaction, based on a study of 192 guests at an independent four-star hotel. Two changes were tested, a television with three energy settings and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) in place of the standard compact fluorescent lightings (CFLs).”

Earth Friendly Neighborhood/Cityscape Design

- What design features prompt people to drive between places that are within walking distance of each other? Schneider found that in shopping districts “respondents were significantly more likely to walk when the main commercial roadway had fewer driveway crossings and a lower speed limit” (2015).

- Cho and Rodriguez (2015) investigated walkability, finding that “conducting research on a neighbourhood scale has been the dominant approach whereas the association of the regional-scale environment with behaviours has rarely been explored. . . . this study [found] that a neighbourhood’s location may be associated with walking or physical activity and that this association may be separately identifiable from the influence of the neighbourhood built environment on behaviours.” So, a neighborhood’s location can have an influence on whether people walk there that’s separate and distinct from the influence of the design of that neighborhood on walking: “residing in a highly urban location had a consistently positive association with walking and transportation-purpose physical activity [regardless of neighborhood design and socio-economic concerns].”

- Whether older individuals decide to walk through a community is tied to the verbal messages they receive related to traveling through it on foot. Walking by elderly people in communities “unfavorable to walking” was measured at the start of Notthoff and Carestensen’s 2017 study and after 4 weeks, using pedometers. People participating in the study “were informed about either the benefits of walking or the negative consequences of not walking. . . . When perceived walkability was high [as determined by the Neighborhood Walkability Scale], positively framed messages were more effective than negatively framed messages in promoting walking; when perceived walkability was low, negatively framed messages were comparably effective to positively framed messages.”

- Brookfield probed how resident preferences align with neighborhood design elements that have been tied to walkability (2017). She found, after conducting focus groups with eleven residents’ groups with diverse sets of participants, that “Residents’ groups favoured providing a selection of services and facilities addressing a local need, such as a corner shop, within a walkable distance, but not the immediate vicinity, of housing. . . . Participants wanted their homes to be ‘insulated’ from the perceived disturbance noise, traffic, parking, anti-social behaviour of non-residential uses by a ‘buffer’ of residential properties. . . overall the majority preference was for one that would take 10 to 15 minutes to cross on foot. . . . Uses such as offices, hotels, supermarkets, nightclubs, industry, warehousing and waste management were opposed in residential areas partly because they were assumed to introduce unwelcome noise. . . . traffic, pollution, parking problems and anti-social behaviour. . . . . a strong preference for green, leafy residential environments was identified. . . . . Providing housing at high densities ‒specifically flats and small, tightly packed houses providing no private outdoor space was uniformly seen as unappealing and problematic.”

- Alfonzo reports on recently completed research indicating that there are financial reasons, in addition to psychological and health ones, to design in walkability (2015). As she details “Walkability is no longer something that is merely nice to have or a luxury; it is a key to economic competitiveness. Millennials and seniors are leading the charge. A Transportation for America survey shows that 80 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds want to live in walkable neighborhoods, and an AARP survey found that an average of 60 percent of those over 50 want to live within one mile [0.6 km] of daily goods and services.” Many additional statistics indicating the financial benefits of walkable design are included in Alfonzo’s article.

- For more information on designing for walkability, read this article.

- Li and Joh have identified a positive relationship between home values, the bikeability of neighborhoods, and the presence of viable public transit: home values increase with bikeability and feasible transit options (2017). As Li and Joh report, “Planners and policy makers are increasingly promoting biking and public transit as viable means of transportation. The integration of bicycling and transit has been acknowledged as a strategy to increase the mode share of bicycling and the efficiency of public transit by solving the first- and last-mile problem. . . . This study [assessed] the property value impact of neighbourhood bikeability, transit accessibility, and their synergistic effect by analysing the single-family and condominium property sale transactions during 2010–2012 in Austin, Texas, USA. . . . to quantify neighbourhood bikeability and transit accessibility, we use Bike Score and Transit Score as publicly available indices. . . . The results from this research show that jointly enhancing bikeability and transit accessibility can generate positive synergistic effects on property values.”

- Repositioning the distribution points for bicycles and increasing the number of bikes available could increase ridership in bike-sharing programs by almost 30%. A press release from the University of Chicago’s Booth business school (“Location, Location, Location: Bike-Sharing Systems Need to Revamp to Attract More Riders,” 2015), indicates that “Although bike-sharing systems have attracted considerable attention, they are falling short of their potential to transform urban transportation. . . . it is possible for cities to increase ridership without spending more money on bikes or docking points—simply by redesigning the network. . . . [Researchers] studied the effects on ridership of station accessibility, or how far the commuter must walk to reach the station, and bike-availability, or the likelihood of finding a bike at the station [in Paris]. The team observed 349 bike stations every two minutes and gathered a total of 22 million data snapshots, or the equivalent of 2.5 million bike trips. . . . [They] determined that a 10 percent reduction in distance traveled to access a bike-share station can increase ridership by 6.7 percent, and that a 10 percent increase in bike-availability can increase ridership by almost 12 percent. By taking these commuter preferences into account, the central Paris bike-share system could increase ridership by 29.4 percent.”

- For more information on designing for bikeability, read this article.

- Yang and colleagues (2015) found in a Missouri based study that “having transit stops within 10–15 min walking distance from home . . . [was] associated with commuting by public transit. . . . Having free or low cost recreation facilities around the worksite . . . and using bike facilities to lock bikes at the worksite . . . were associated with active commuting [riding bicycles to work, etc.].”

Material Spotlight:Sustainable Wood Grain

Wood is the natural material whose use has been most extensively researched by neuroscientists and which can be an earth friendly design option. Researchers have learned a great deal about how our thoughts and behaviors are affected by wooden surfaces, particularly the wood grain patterns visible on them.

The Psychology of Wood:Fundamentals

- Seeing wood grain is a stress-reducing experience (Fell, 2010). David Fell’s dissertation project investigated the psychological influence of wood in interior spaces. Fell found evidence that “wood provides stress-reducing effects similar to the well studied effect of exposure to nature in the field of environmental psychology.” This leads to the conclusion that “wood may be able to be applied indoors to provide stress reduction as a part of the evidence-based and biophilic design of hospitals, offices, schools, and other built environments.” This information is particularly important because wood can be used in any sort of space—for example ones without views of nature or ones that cannot support plants. The wood included in the test environment was birch veneer office furniture with a clear finish.

- People seem to be both more relaxed in spaces featuring wooden surfaces and also better able to concentrate in them (Augustin and Fell, 2015, reporting on work done by Yuki Kawamura not yet published in English).

- Covering about 45% of surfaces with wood seems to be a magic dose. In a 2007 study, Tsunetsugu, Miyazaki, and Sato measured blood pressure in rooms where 0%, 45%, or 90% of surfaces were covered with wood with visible grain. While blood pressure was lowest in the room with 90% wood surfaces, the room with 45% wood surfaces was preferred by study participants and this was the room that was rated as most comfortable. In a study conducted by Masuda and Yamamoto in 1988, people looked at photos of living rooms and evaluated the spaces viewed. Rooms were rated as more pleasantly relaxed as the percent of surfaces covered by wood increased to 43%; after that relative amount of wooden surfaces, spaces were seen as less warm (i.e., pleasantly relaxed).

- In cooperation with a research team at the Technical University of Munich, Stora Enso (2020) released a white paper detailing health and wellbeing benefits of living and working in spaces with wood design elements. Research indicates, for example, that “wood has beneficial effects. . . . It helps reduce stress, blood pressure and heart rate as well as allowing for more creativity and productivity in the workplace. Wood is also an important part of what’s called biophilic design; our desire to be connected with the natural environment.”

- Terrapin Bright Green has compiled an introduction to some of the research on wood-related topics of interest to designers (Browning, Ryan, and DeMarco, 2022). As the Terrapin team state in the abstract for their text, “In the design sphere, an awareness of the physiological and psychological impacts of wood products and structures is beginning to take hold. By asking why we love wood, The Nature of Wood explores the science of having a ‘biophilic’ response to wood.” Many findings familiar to readers of Research Design Connections are shared in the report; for example, “While there is some indication of there being cultural variations to wood color preference, warmer colors hold the majority preference. It is intriguing that the preferred color range of yellow to red is said to be warm, but also calming.”

Wood in Healthcare Spaces

- When furniture with visible wood grain is used in hospital rooms, those rooms are rated as more appealing than when the wooden furniture is not present (Swan, Richardson, and Hutton, 2003). Also, when wooden furniture is in place, doctors and patient food are evaluated more positively than they are when it’s not.

- Hospitals have been adding hotel-like amenities for some time; new research indicates their value to patients (Bird, 2016). Suess-Raeisinafchi and Modv found that “patients are willing to spend 38 percent [out of pocket] more for a hospital room if it has the right kind of hotel-quality upgrades.” Researchers “surveyed about 400 people online, all of whom had been in a hospital in the past six months. Participants looked at 40 custom-designed renderings of hospital rooms, containing various combinations of hotel amenities.” Amenities investigated included “interior design, health care service, and food options.” The amenity with the most impact on room preference was “interior design. Participants preferred hospital rooms that had an updated, modern look, like an accent wall or wood-laminate floor. Second was hospitality-trained staff, and third was the technology available, like a high-quality flat-screen TV. . . . [Suess-Raeisinafchi] notes that this study builds on a body of research showing that hotel-like rooms and hospitality-trained staff in hospitals can actually improve patient outcomes.” Although overall those surveyed were willing to pay 38% more out of pocket for a room with hotel-like amenities than for a standard room, “there was also a split between what ‘less healthy’ and ‘more healthy’ patients would pay. ‘Less healthy’ survey participants, who had spent more time in the hospital and rated their own physical and mental health lower than a ‘more healthy’ group, were willing to pay 44 percent more for a hotel-like room, compared to only 31 percent more for the ‘more healthy’ group.”

Wood in Schools

Kelz, Grote, and Moser studied stress levels in Austrian classrooms, and learned that students were less stressed in classrooms that used predominantly wood finishes than students in classrooms that were not wood-dominate (2011).

Workplace Use of Wood

- Using wood in commercial lobbies seems like a good idea. Ridoutt and colleagues published studies in 2002 reporting that “Firms with wooden finishes in their reception areas were seen as more prestigious than those using other materials, as well as more energetic, innovative, and comfortable. Firms using wood materials in their lobbies were felt to be more desirable organizations to work for” (quote from Augustin and Fell, 2015).

- Work by Maier and colleagues (2022) confirms that workplace design influence opinions formed of firms. They report that “creative workspace design has a positive effect on organizational attractiveness. . . . this attraction effect is stronger for highly creative (vs. less creative) individuals. . . . creative workspaces featured significantly more unconventional characteristics than the conventional offices, including cheerful colors, indoor plants, large windows, views of nature, flexible workspace arrangements, natural elements (e.g., wood, stone), fun elements (e.g., toys, table soccer . . .) . . . and unconventional decorative elements (e.g., wall-mounted bicycles). . . . high-value workspace conditions showed high-end equipment such as designer leather chairs, comfortable workstations with the latest technologies, and premium materials (e.g., solid wood furniture). In contrast, low-value workspaces showed cheaper office equipment made of standard materials or self-assembly furniture (e.g., plywood desks) with basic technologies and standard office chairs. . . . both companies with high-value and low-value workspaces can benefit from the integration of creative elements into their office.”

- Poirier and Demers (2019) probed human responses to viewing wood of various colors/finishes in daylight. Images of the room mockups assessed by participants in their studies are available at the website noted below. The researchers found that when “participants compared simultaneously five different interior wooden scale models of room environments under the natural light of the northern hemisphere . . . . Conclusions showed a preference for clear, bright, and warm models for cognitive . . . tasks. Darker models in terms of reflectance and lighting ambiences were the least preferred, especially for women. . . . Warm, bright, and clear spaces can enhance inhabitants’ concentration and cognitive tasks, whereas dark and contrasted spaces can considerably reduce the inhabitants’ comfort and psychological well-being. . . . The scale models are made with different combinations of wooden panels, using three different colors namely cape cod gray (a gray, neutral, and cold finish), oak (a yellow, warm, and bright finish), and dark walnut (a brown, dark, and neutral finish). Each wooden panel is found in two types of finish: high gloss (90°) and low gloss (12°).”

- Zhang, Lian, and Ding (2016) collected data in four different test rooms. In one, all interior walls were steel painted white. Three other spaces had varying numbers of unpainted, wooden walls, but in each of these three conditions, the data collected were comparable. These three spaces, all categorized as “wooden” had walls that were either covered 100% with dark brown wood (which looked a lot like tree bark and had a rounded, log like shape), 100% with light brown wood (which looked a lot like planed planks), or a mix of 50% light brown wood and 50% white-painted steel. The ceilings in the test rooms were not described. The difference between the test rooms with all white walls and those with some—or all—wooden walls seems quite dramatic and it would have been interesting to see comparisons between, for example, experiences in rooms with walls painted brown and in ones with wooden walls. Zhang, Lian, and Ding found that after people had been in the environments tested for an hour “More positive emotions were generated in wooden environments than in non-wooden environments. . . . fatigue evaluation values of wooden environments were dramatically lower than those of non-wooden environments after continuous working [mental effort], which implied that the participants in wooden environments suffered from less fatigue. . . . Compared to non-wooden rooms, wooden ones were considered as more comfortable environments.”

- Burnard and Kutnar (2020) evaluated links between wooden furniture and employee wellbeing; and their work supports using lighter finishes on wooden surfaces. They determined that when “human stress responses were compared in experimental office settings with and without wood. . . . as indicated by salivary cortisol concentration. . . . overall stress levels were lower in the office-like environment with oak wood than the control room [white furniture], but there was no detectable difference in stress levels between the office-like environment with [American] walnut wood and the control room. . . . it is possible to use wood furniture as a passive environmental intervention to help office workers cope with stress. However, when selecting wood furniture, it is important to consider visual characteristics, amongst other aspects, and how they interact with other elements of the indoor environment (e.g. lighting). The oak furniture used in this experiment was noticeably lighter in colour and produced a noticeably brighter environment than the office with walnut furniture, even though lighting levels were the same in each room.”

- When asked, people stated that they felt they would be more creative in a space featuring wood grain or stone surfaces than they would be in areas without these finishes (McCoy and Evans 2002).

Residential Use of Wood

- Porch commissioned research which reveals differences—and similarities—in European and American opinions about home design (2018). Their findings, derived after interviewing over 600 people living in the US and Europe about ideal home design, include “For nearly 45 percent of Americans and 52 percent of Europeans, the choice was clear: Waterfront views took home the grand prize. . . . while the ideal home size for Europeans was nearly 1,590 square feet, Americans felt they needed a home over three times that size—4,982 square feet, on average. . . . According to Americans and Europeans, the ranch house design was the most popular exterior style. . . . .The farmhouse and craftsman styles ranked highest for Americans . . . while Europeans opted for cottage- and Mediterranean-style homes instead. . . . Both Americans and Europeans favored wood flooring over any other option. . . . Americans were more interested in having centralized air conditioning and a laundry room, while Europeans favored solar panels, swimming pools, and libraries.” Porch shares that “This project relied on self-reporting, and the findings have not been statistically tested. Therefore, these results are intended for entertainment purposes only.”

- Cox has investigated properties that people link to homier environments, and her findings are relevant to the full range of spaces where people will live, even temporarily. As a press release (“What Makes a House a Home,” 2016) from the publisher of Cox’s study (Home Cultures journal) states: “Rosie Cox’s study in Home Cultures explores property owners’ notions of ‘home’ and their home making journeys and argues that sometimes what is ‘homey’ about a home is its very lack of robustness. . . . Cox interviewed 30 homeowners from New Zealand about their home improvements. . .. She explored what motivated their home renovations and the division of labour. Surprisingly, most did not want a perfectly fortress like house but preferred to put their own stamp on it through self-improvements and felt they did not truly ‘own’ it until they had. . . . many expressing a preference for more malleable materials such as wood over concrete or steel.”

- In tests in a bedroom, Kawamura measured melatonin levels in people in three situations: under direct artificial light and when artificial light was bounced off a white ceiling or a ceiling with wood grain. Melatonin levels were highest when the light reflected off the wood, which means people there would fall asleep faster (Augustin and Fell, 2015, reporting on work done by Yuki Kawamura not yet published in English).

- Furhapper and colleagues (2020) investigated the experience of living in newly-built timber homes. They conducted a “study [that] included a comparison of the construction types timber-frame (TF) and solid wood (SF), in addition two different ventilation types, controlled vs. window ventilation. . . The emission progression of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) including formaldehyde, was recorded and compared with the subjective well-being of the residents . . . VOC-emissions were initially elevated regardless of construction and ventilation type. However, after a period of up to 8 months emissions mostly decreased to an average level. . . . The use of controlled ventilation systems resulted in lower VOC-concentrations and thus in higher IAQ compared to window ventilation. From a toxicological point of view the major part of the investigated houses were unobtrusive and IAQ was considered as ‘high’ or ‘satisfactory.’ Residents were continuously very satisfied with their health and quality of life. This perception was confirmed by the results gained from the accompanying medical examinations.”

More Insights Related to Wood

- Cosgun and associates (2022) set out to learn how wall coverings influence perceptions of cafés. They report on a virtual reality based research project: “This study aims to determine the effects of wall covering materials (wood, concrete and metal) used indoors on participants’ perceptual evaluations. . . . Cafes using light-coloured wall covering materials were perceived more favourably than cafes using dark-coloured wall covering materials, and cafes with light-coloured wooden wall coverings were considered as a warmer material (sic) than cafes using concrete and metal.”

- Gade (2015) shares that “Certain features regarding hall design are often expressed by musicians. Halls with exposed wooden surfaces are often well liked, probably because wood is being associated with warmth and resonance as is the case with the wooden body of stringed instruments.” Also, “Besides the influence of acoustics on the perceived tonal color, one cannot neglect a coupling between our hearing and vision. For sure our impression of tonal color will also be influenced by the colors we see in the hall. Deep red or brown (wooden) walls will probably ‘sound’ warmer than pale green walls—illuminated with ‘cold’ neon lights.”